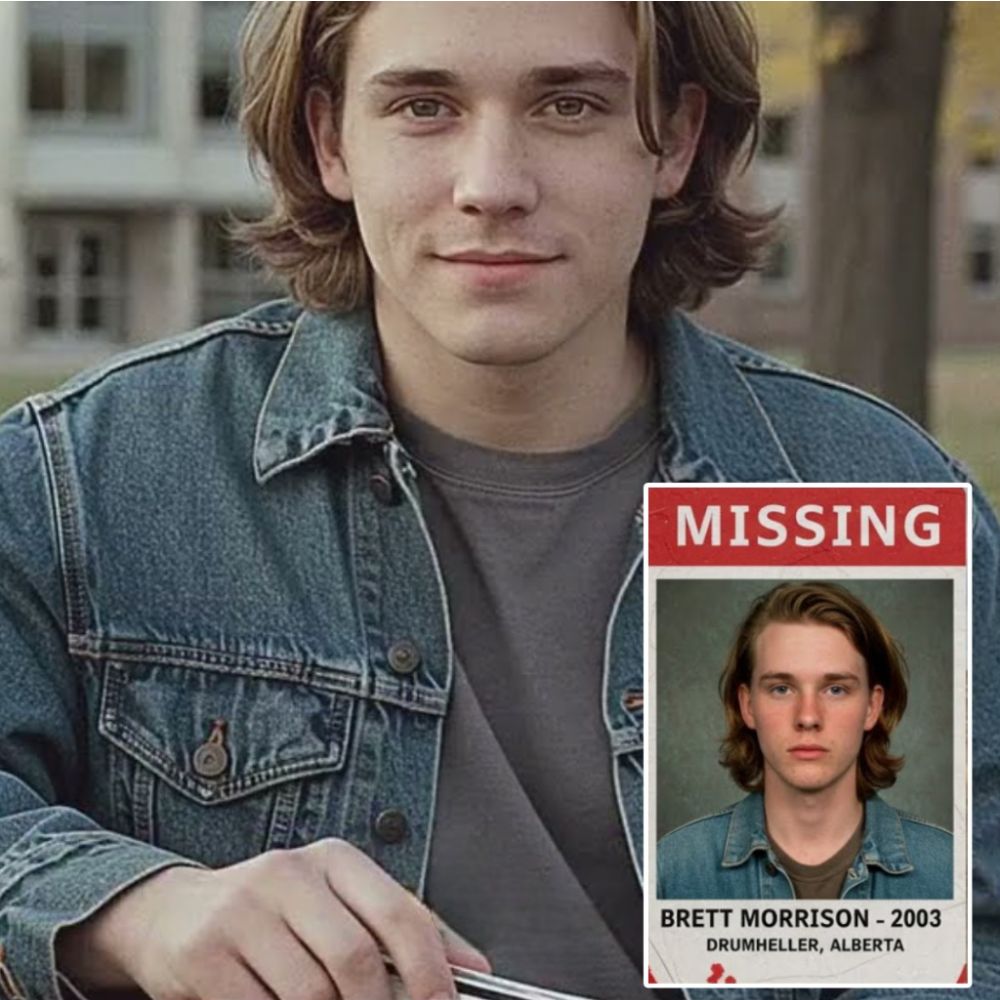

Alberta 2003 case cold solved — arrest shocks community

The Last Phone Call

The last person to see Brett Morrison alive said he looked back once before vanishing into the dark Alberta night — and in that fleeting glance, something in his eyes didn’t look right. It wasn’t fear, exactly. It was resignation.

That was October 17, 2003 — a date that would become a scar on the quiet town of Drumheller, Alberta, where the prairie stretches forever and the wind whispers secrets no one wants to hear. For nearly two decades, the disappearance of the 18-year-old American forestry student from Portland, Oregon, haunted investigators, destroyed a family, and turned into one of Canada’s most enduring unsolved mysteries.

Until now.

Sixteen years later, a single anonymous letter reopened the case — and what investigators uncovered would shake the town, the university, and everyone who thought the truth was buried forever.

The Disappearance

In 2003, Brett had just begun his studies at a small technical university outside Drumheller, hoping to specialize in forestry management. He was quiet, polite, and fiercely determined — a kid who preferred books to parties, and observation to conversation.

On the evening of October 17, Brett received a brief phone call on his dorm room landline. His roommate, Owen MacLeod, was at the library. When he returned an hour later, Brett was gone — his bed untouched, his hiking boots missing, a duffel bag left behind.

“He said he was going to the old grain elevator,” Owen later told police. “He looked scared. But… like he’d already made up his mind.”

The grain elevator stood four kilometers east of campus — an abandoned, graffitied structure kids whispered about but rarely approached. Locals said it had bad energy. By sunrise, Brett’s roommate had filed a missing persons report.

When police arrived, the elevator was sealed, its chains rusted shut. There were no footprints, no discarded belongings, no sign Brett had ever made it there.

The Search

For weeks, RCMP officers, students, and locals scoured the badlands — a harsh landscape of coulees, clay cliffs, and hoodoos carved by wind and time. Helicopters flew overhead. Volunteers combed the ravines. But winter came early that year. Temperatures plunged, and hope froze with the ground.

Then, seven days after Brett vanished, a rancher east of Drumheller found something fluttering in his fence line: a denim jacket.

Inside one pocket was a wallet with an Oregon driver’s license — Brett Morrison.

The RCMP redoubled their search. Dogs tracked his scent toward a deep ravine nearby, but found nothing. No blood, no body, no tracks. The prairie, it seemed, had swallowed him whole.

By winter’s end, the case went cold.

A Town of Secrets

From the beginning, investigators suspected Brett’s disappearance was linked to a university hazing ritual known as “Initiation Night.” Older engineering students would secretly test first-years — blindfolds, pranks, and forced night hikes into the prairie.

No one would talk.

Rumors swirled about a ringleader named Travis Bauer, a popular upperclassman known for pushing limits, and about Dr. Leonard Fisher, a respected professor who oversaw field trips.

Students whispered that Brett’s name had been chosen precisely because he was an outsider — the American kid who wouldn’t tattle.

Detectives questioned Bauer, his friends, and Dr. Fisher. Every one of them denied involvement.

Then, a week later, a janitor claimed she’d seen Bauer and another student, Cole Murphy, leaving the Earth Sciences building before dawn the morning after Brett disappeared — even though the building was supposed to be locked.

Still, no arrests.

Sixteen Years of Silence

The case languished in filing cabinets for sixteen years. Brett’s mother, Carol Morrison, refused to move on. She built a website, FindBrettMorrison.com, and returned to Drumheller every October, leaving candles near the grain elevator.

Locals pitied her. Others wished she’d stop reminding them of what they’d tried to forget.

Then, in March 2019, a plain white envelope arrived at the Drumheller RCMP detachment. Inside was a single sheet of notebook paper:

“I know where the American student is buried.

He didn’t die by accident. People covered it up.

Check the old Fisher property.”

It was unsigned. But it changed everything.

The Old Fisher Property

Detective Sergeant Emma Gallagher was assigned the cold case. A seasoned investigator with Major Crimes, Gallagher wasn’t easily spooked. But something about the letter’s specificity — naming Fisher, referencing a property long sold — made her blood run cold.

Property records showed that Dr. Leonard Fisher, now retired and living on Vancouver Island, had once owned a 160-acre farmstead northeast of Drumheller. It had sat abandoned for years before being sold to a cattle company in 2006.

In May 2019, RCMP forensic teams brought in ground-penetrating radar. On the third day, they found an anomaly six feet below the surface, near the collapsed wall of an old barn.

By dusk, they were digging.

They unearthed human remains wrapped in what had once been a tarp. DNA matched a sample from a toothbrush Carol Morrison had preserved for sixteen years.

It was Brett.

The Forensics

Forensic anthropologists confirmed what Carol had always feared: Brett hadn’t died by accident.

His skull showed signs of blunt force trauma — a blow that would have disoriented him but not killed him outright. The cause of death was listed as hypothermia complicated by head injury.

He’d been left alive long enough to freeze to death.

The manner of burial — deliberate, careful, hidden — indicated intent to conceal, not grief.

And the property? Still registered to Dr. Fisher at the time of Brett’s disappearance.

Digital Ghosts

When Gallagher subpoenaed the university’s old email archives, she uncovered a chilling thread from October 2003 between Fisher and several students:

“Use the old location we discussed,” Fisher wrote to Bauer. “No one goes out there. Just make sure everything is cleaned up after.”

The “old location” was the same rural property where Brett was later found.

Recovered logs showed Fisher had accessed his university computer hours after Brett disappeared, and deleted dozens of files over the next several days.

The digital trail painted a damning picture — a professor using authority and access to help his students hide a deadly mistake.

But Gallagher still lacked one thing: a witness willing to break the code of silence.

The Confession

That witness came in the form of Cole Murphy, now 37, married, and a successful civil engineer in Edmonton.

When Gallagher approached him at his office, he didn’t even pretend ignorance. “I knew this day would come,” he said quietly. “I didn’t kill him. But I helped cover it up.”

Over two hours, Murphy’s story poured out.

He said Brett had been lured to the grain elevator under the guise of initiation. There, upperclassmen — including Bauer, Ryan Boyle, Tyler Gordon, and Marcus Hamilton — blindfolded him and drove him into the prairie, telling him to find his way back as a “test.”

At some point, Brett fell into an abandoned well, hitting his head. When they found him, he was bleeding but conscious. Instead of calling for help, they called Fisher.

Fisher told them not to involve police. He said Brett wasn’t badly hurt, that hospitals meant “questions and consequences.” He told them to bring the boy to his rural property, where he’d keep him warm through the night.

By morning, Brett was dead.

The Cover-Up

Fisher told the panicked students they had two choices: report the death and destroy their futures, or bury it — literally — and move on.

They chose silence.

He instructed them to dig behind the barn. He wrapped Brett’s body in a tarp. And before dawn broke, the prairie swallowed another secret.

For sixteen years, five men lived with it — one of them, Marcus Hamilton, drank himself to death in 2011.

When guilt finally cracked Murphy open, the others soon followed. Boyle confessed. Gordon turned himself in from Australia, bringing his old journal — entries written in 2003 detailing Fisher’s orders:

“Doctor F said hospital means police, investigations, destroyed futures. Or we handle it ourselves.

We chose ourselves over Brett.”

Justice at Last

By October 2019, the RCMP arrested Dr. Leonard Fisher, now 73, at his home in Nanaimo. His charges: criminal negligence causing death, accessory after the fact, indignity to human remains, and obstruction of justice.

Bauer, the student ringleader, was arrested the same day in British Columbia. Murphy, Boyle, and Gordon accepted plea deals for reduced sentences in exchange for testimony.

The trial began in March 2021 in Drumheller.

It captivated the nation.

For weeks, jurors listened to confessions, journal entries, and emails that chronicled the transformation of a prank into a crime — and a cover-up that spanned continents and decades.

Fisher took the stand, admitting he’d helped bury Brett but insisting he’d believed the boy would survive. “It was a tragic mistake,” he said.

Prosecutor Margaret Fitzgerald countered with cold precision: “A mistake is forgetting an appointment, Doctor. You buried a living boy.”

The Verdict

On April 19, 2021, after four days of deliberation, the jury returned its verdict:

Guilty of criminal negligence causing death

Guilty of accessory after the fact

Guilty of indignity to human remains

Guilty of obstruction of justice

Not guilty of manslaughter

Fisher was sentenced to 22 years in prison — effectively life. Bauer received 18.

When asked if she forgave him, Carol Morrison said simply, “No. But now my son can rest.”

The Legacy

Brett Morrison’s remains were laid to rest in Portland, Oregon, in June 2021. His headstone reads:

“Beloved Son — Found at Last.”

The university has since installed a permanent memorial in his name and banned all initiation rituals. Each year, new students hear Carol Morrison speak about the cost of silence.

For Drumheller, the case left a lasting shadow — a reminder that secrets buried in small towns don’t stay buried forever.

Because the prairie, as locals say, keeps what it takes — but sometimes, just sometimes, it gives one back.