Before the butcher of Plainfield, there was the woman who made him.

The story of Ed Gein has long been carved into the dark mythology of American crime — a tale that inspired Psycho, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and countless nightmares.

But before the world ever knew his name, there was Augusta Wilhelmine Gein — his mother, his prophet, and, in many ways, the architect of his madness.

Augusta wasn’t merely strict. She was a force of nature — a thunderstorm of righteousness, resentment, and religious terror.

Her influence would twist a lonely boy from rural Wisconsin into one of the most notorious figures in criminal history.

And it all began, as such stories often do, inside a quiet farmhouse at the edge of the world.

The Gospel According to Augusta

Born in 1878 to German immigrants, Augusta was raised in an atmosphere of hardship and piety.

By adulthood, her faith had hardened into something unrecognizable — not devotion, but domination.

She carried a Bible everywhere, underlined passages about sin and punishment until the pages turned thin as onion skin.

To Augusta, women were the root of corruption — “instruments of the devil,” she once called them.

Except, of course, for herself.

Her husband, George Gein, was everything she despised: a drunk, a failure, a man whose weakness confirmed her certainty that only she could lead her family to salvation.

By the time they married, Augusta’s love for George had curdled into disgust.

She referred to him as “the animal” and prayed daily that God might grant her strength to endure him.

But she didn’t leave.

She ruled — and she made sure her sons learned what it meant to live under holy fear.

Life on the Gein Farm

In 1914, the Geins settled on a 155-acre farm just outside Plainfield, Wisconsin.

It was isolated — surrounded by cornfields, forests, and a silence so heavy it pressed against the windows.

To Augusta, the isolation was perfect.

No neighbors to corrupt her sons.

No city women to tempt them.

No laughter, no parties, no sin.

She banned visitors, burned magazines that contained pictures of women, and discouraged all forms of play.

Instead, she taught Henry and Edward about the evils of desire and the punishments of hell.

Every evening, she gathered them in the parlor to read Scripture aloud, her voice echoing over the ticking of a clock and the crackle of the fire.

“The world is filth,” she’d say. “Only we are clean.”

The boys listened — but not equally.

Henry, the elder, grew skeptical as he aged.

Ed, the younger, absorbed every word.

A Son’s Devotion

Neighbors would later recall Ed Gein as quiet, shy, almost delicate.

He blushed when spoken to, laughed nervously when teased.

While other boys hunted or courted girls, Ed stayed home, milking cows, fixing fences, tending to Augusta’s every command.

He adored her.

He worshipped her.

He feared her.

If she smiled, he felt holy.

If she scolded him, he felt damned.

When she spoke about women, Ed listened with reverence and confusion.

She told him that all women — except herself — were impure, temptresses, corrupters of men.

She warned that lust led to eternal fire.

And yet, as Ed entered his teens, he began to feel desires he couldn’t reconcile with her teachings.

Every time he looked at a girl, guilt burned hotter than the feeling itself.

He would run home and beg Augusta to forgive him.

She would.

But her forgiveness came laced with humiliation.

“You are not like other men,” she’d whisper. “You are mine.”

A Kingdom of One

As the years passed, George’s drinking worsened.

He became violent, unpredictable — but Augusta never wavered.

She believed his downfall was divine proof of her righteousness.

When he died in 1940, she barely cried.

Now the farm was entirely hers.

And Ed — at 34 — was her servant, her confidant, her child.

Neighbors found it strange that a grown man never left home, but in Plainfield, people minded their own business.

When asked why Ed didn’t marry, Augusta said coldly, “No decent woman would want him, and I will not see him taken by a whore.”

So Ed remained.

Cooking. Cleaning. Listening.

The house became a kingdom of two — Augusta the queen, Ed her devoted subject.

But in every kingdom ruled by fear, something eventually breaks.

The Death of Henry

In 1944, tragedy struck.

A brush fire spread across the Gein property, and both brothers went out to control it.

When it was over, only Ed returned — claiming he’d “lost sight” of Henry.

Searchers found Henry’s body face-down on scorched ground.

Though there were no burns, his head bore strange bruises.

The coroner listed the cause of death as asphyxiation.

No investigation followed.

Some whispered that Ed might have “helped” his brother die.

After all, Henry had begun speaking ill of Augusta — calling her controlling, even insane.

If Ed heard such blasphemy, what would a son who saw his mother as divine do?

We’ll never know.

But after Henry’s death, Augusta had Ed entirely to herself.

The Saint and the Sinner

In her final years, Augusta grew ill and paranoid.

She suffered a stroke that left her weak but no less domineering.

She spent her days in her rocking chair, reading her Bible aloud and cursing the “wickedness of women.”

One day, she and Ed visited a neighbor’s house, where a woman was present.

The woman, kind and cheerful, offered them coffee.

Augusta exploded.

When they returned home, she ranted for hours, calling the woman “Jezebel,” accusing Ed of lust simply for looking at her.

It was the last major outburst of her life.

Weeks later, she suffered another stroke — and died.

Ed was inconsolable.

He fell to the floor beside her bed and sobbed for hours.

Then, slowly, he sealed her room shut — as if she had merely stepped out and would one day return.

No one entered again for years.

The house began to decay. So did Ed.

The Descent Begins

With Augusta gone, Ed drifted like a man without gravity.

He lived alone, scraping by with odd jobs — handyman work, farm chores, the occasional babysitting.

People called him “weird but harmless.”

He spent nights reading pulp magazines and anatomy books.

He clipped obituaries of recently deceased women.

He visited the local graveyard under moonlight, saying he “needed to see” them one last time.

By 1954, whispers had become rumors.

Children said they saw lantern light in the cemetery after midnight.

Hunters claimed they heard shovels scraping dirt.

No one wanted to believe it.

Until they had to.

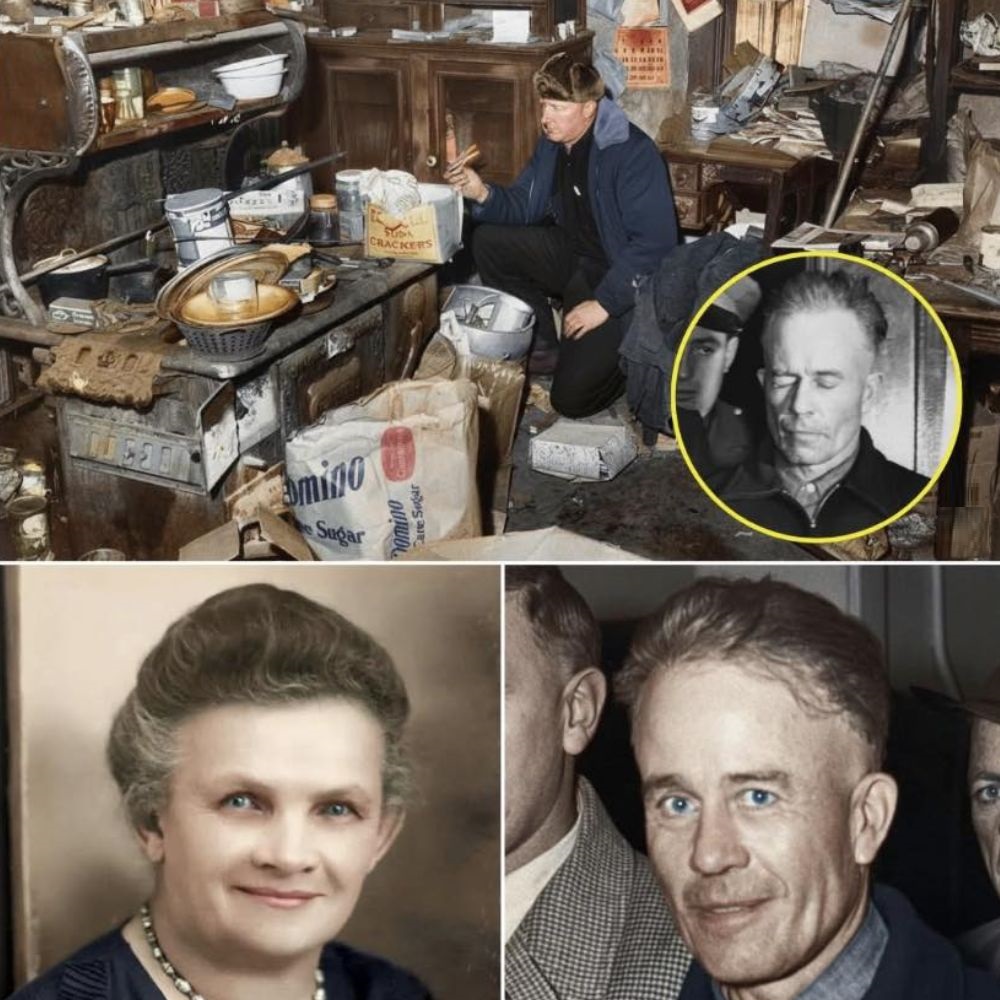

The Night the Masks Fell

On November 16, 1957, Plainfield hardware store owner Bernice Worden vanished.

The store was empty except for a blood trail leading out the back door.

The last receipt written in her ledger was for antifreeze — sold to Ed Gein.

That evening, police arrived at the Gein farmhouse.

What they found inside defied imagination.

The house was a tomb of horrors.

Skulls turned into bowls.

Chairs upholstered with human skin.

A belt made from nipples.

And in a shed behind the house, Bernice Worden’s body — decapitated, hanging upside down like a slaughtered deer.

When officers asked why, Ed answered simply,

“I wanted to see what she looked like on the inside.” The Ghost of Augusta

During questioning, Ed spoke about his mother constantly.

He described her as “the only woman who ever loved me.”

He said the others — the women he dug up — “reminded me of her.”

He denied killing most of them, insisting he’d only “borrowed” their bodies from graves.

He claimed he made skin masks and suits to “be close” to Augusta again — to become her, to feel her presence.

“When I wear the skin,” he said, “I feel like she’s still here.”

Psychiatrists later called it a psychosis born of repression and isolation — the grotesque flowering of a lifetime under religious terror.

But others saw something simpler and more sinister: a son who never escaped his mother’s voice.

The Making of a Monster

When the news broke, the world fixated on Ed Gein — the quiet farmer turned ghoul.

Reporters called him “the Butcher of Plainfield,” “the Grave Robber,” “the Mad Skinmaker.”

But buried in the coverage was the deeper question: how did he become this?

The answer lay in the farmhouse long before the crimes.

It lay in Augusta’s sermons, in her fury, in her unyielding grip on her son’s soul.

Every rule she enforced, every fear she planted, stripped Ed of humanity.

Desire became sin.

Curiosity became guilt.

Obedience became worship.

Psychologist Dr. Helen Roth, who studied the case years later, put it plainly:

“Augusta Gein didn’t raise a son. She built a shrine — and locked him inside it.”

When that shrine collapsed with her death, Ed filled the emptiness with corpses.

He recreated her world in flesh because he no longer knew any other way to feel love.

The Farm as Symbol

When investigators photographed the Gein farmhouse, the images revealed more than crime; they revealed metaphor.

Augusta’s room — immaculate, preserved, untouched — stood like a cathedral.

Everywhere else was decay: rot, filth, bones, skin.

It was as though the house itself had split in two — purity versus corruption, mother versus world, heaven versus hell.

And in the middle stood Ed, the high priest of his mother’s religion, performing rituals of death in her name.

Even the neighbors, once horrified, began to speak of Augusta with equal dread.

“She was meaner than he was,” one old farmer told reporters. “That boy never had a chance.”

The Psychological Prison

Experts would later classify Ed Gein’s condition as psychotic necrophilia combined with acute maternal fixation. But clinical terms barely touch the emotional terror that defined his life.

Imagine growing up believing every woman is evil — except the one who controls you.

Imagine feeling love as a form of sin.

Imagine the only intimacy you’re allowed being fear.

When Augusta died, Ed’s world collapsed not because he lost his mother, but because he lost his god.

He didn’t kill for pleasure. He killed to rebuild the altar.

Legacy of Fear

After his arrest, Ed Gein was declared insane and committed to Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

He remained there for the rest of his life — quiet, polite, occasionally smiling when asked about his mother.

Visitors said he often spent hours cutting out photos of women from old magazines, gluing them into collages shaped like hearts.

When nurses asked why, he said, “They remind me of home.”

Augusta’s legacy lived on — not only in him but in the culture she indirectly birthed.

From Norman Bates’s obsession in Psycho to Leatherface’s faceless horror, Hollywood turned the Gein myth into modern folklore.

But behind every retelling, there remains the shadow of that farmhouse — and the woman who ruled it.

A Monster Made, Not Born

In the decades since, criminologists have debated whether Ed Gein was a product of insanity or of upbringing. Most agree it was both.

He was mentally ill, yes — but his illness had fertile soil. Augusta’s home was that soil.

Her obsession with purity planted the seeds of disgust.

Her isolation nurtured delusion.

Her sermons watered guilt until it grew into madness.

When she forbade him to touch or love anyone else, she didn’t just imprison him — she created the conditions for obsession. And when she died, that obsession found its outlet in death.

“Evil rarely begins with the monster,” said Dr. Roth. “It begins with the mother who teaches that love is poison.” Plainfield Today

Today, nothing remains of the Gein farmhouse.

It burned to the ground in 1958 — cause undetermined.

Some say arson; others call it exorcism.

Locals still lower their voices when speaking of it.

The land is overgrown now, reclaimed by weeds and wind.

But on quiet nights, they say, you can still see the faint outline of the foundation under moonlight — a scar in the earth that never quite healed.

Tourists still come to Plainfield, searching for the house, for a piece of the legend.

They leave flowers, prayers, sometimes apologies.

But those who know the story understand that the real horror never lived in that house.

It lived in the mind of a woman who believed she could control sin by destroying love.

The Final Judgment

In the end, Augusta Wilhelmine Gein never wielded a weapon.

She never spilled blood.

She never touched the bodies that would one day be found in her home.

But her fingerprints are everywhere — on every page of Ed’s confession, on every bone the police unearthed, on every scream that echoed through the Wisconsin winter.

She taught her son that the world was wicked, and he proved her right in the most horrific way imaginable.

He became the monster she feared — and, perhaps, the one she created to justify her fear.

Epilogue: The Quiet Aftermath

When Ed Gein died in 1984, his obituary was short, sterile, factual.

No mention of Augusta beyond “predeceased mother.”

But those who studied him knew better.

You cannot bury a mother like Augusta.

You can only survive her — or fail to.

And so, as history turned her son into myth, Augusta remained in the shadows: a warning, a ghost, a reminder that monsters are often forged in silence, beneath crosses, behind locked doors.

Because sometimes evil doesn’t begin with a killer.

Sometimes, it begins with a parent who teaches fear instead of love.