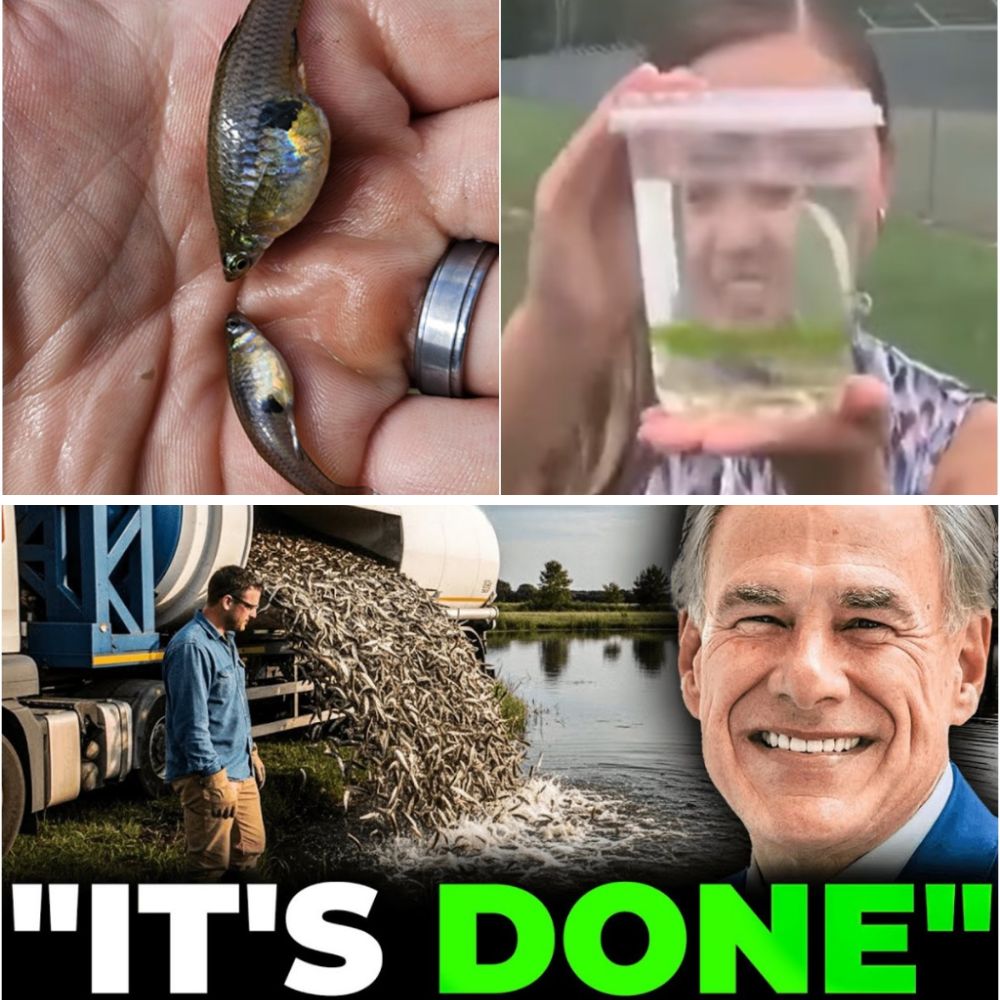

Texas Was Mocked For Dumping Thousands of Mosquitofish Into Ponds. The Results Might Shock Them

When news broke that Texas was dumping thousands of fish into local ponds to fight mosquitoes, the internet had a field day.

“Texas is throwing fish at bugs,” one viral post mocked. Memes flooded X (formerly Twitter), showing cartoon fish wielding fly swatters and nets. Environmentalists questioned the sanity of it all. Critics called it desperate, wasteful, absurd.

But as the laughter died down and the summer heat rose, something unexpected began to happen in those same ponds — something that would turn mockery into awe.

A Summer of Fear

In the summer of 2015, North Texas was roasting. For weeks, temperatures soared above 100°F, and with the heat came an enemy more terrifying than the sun — mosquitoes.

They weren’t just an annoyance. They were carriers of West Nile virus, and the numbers were climbing fast. Dallas County saw infection rates rise to alarming levels, with several deaths reported.

Spray trucks rolled through neighborhoods at night, fogging the streets with pesticides. Homeowners bought out entire shelves of repellent. But the mosquitoes didn’t seem to care. They came back stronger after every round.

Health officials began to panic. Zack Thompson, Dallas County’s Health and Human Services Director, issued a stark warning:

“If we keep spraying at this rate, we’ll create pesticide-resistant mosquitoes — superbugs that no chemical can kill.”

The city needed a miracle. What it got was a fish.

The Plan Everyone Laughed At

At a tense city council meeting, Jeff Heineka, Plano’s Environmental Director, stood up and presented an idea that sounded more like a joke than a strategy: release thousands of mosquitofish into local ponds.

The laughter was instant.

“How would fish stop flying insects?” one council member asked.

“What happens when they die in the Texas heat?” another quipped.

But Heineka stayed calm. He presented studies showing that these small, unassuming fish — Gambusia affinis — had been used successfully to control mosquito larvae for over a century.

Each fish could eat hundreds of larvae a day. They reproduced quickly, thrived in warm, stagnant water, and were native to the southern U.S.

It was an ecological solution in a chemical war.

Still, to many, it sounded ridiculous.

When the plan became public, social media lit up again. “Fish versus mosquitoes” trended for days. Late-night hosts joked about Texas “declaring war on bugs with sushi.” Environmental groups worried about disrupting local ecosystems. Fiscal conservatives demanded to know how much taxpayer money was being wasted on what they called “a fishing expedition.”

But Heineka didn’t flinch. He selected two test sites — Pecan Hollow Golf Course and the Plano Parkway Service Center — and set a date.

Dumping Day

It was a blistering July morning when trucks loaded with giant tanks pulled up to the pond at Pecan Hollow.

Protesters lined the area holding signs that read, “Don’t mess with nature!” and “Fish don’t fly!”

Reporters gathered. Drones hovered. It was part science experiment, part public spectacle.

At 10 a.m., the valves opened. Thousands of tiny, silvery fish poured into the water, glimmering in the sunlight. The crowd held its breath.

“It’s done!” someone shouted — the moment quickly went viral.

But instead of floating lifelessly, the mosquitofish darted beneath the surface, immediately seeking out shaded areas and vegetation — exactly where mosquitoes lay their eggs.

Heineka smiled. “They’re already hunting,” he said.

Still, the skeptics smirked. They wanted data — not hope.

The Waiting Game

Two weeks passed. The story faded from the headlines. But behind the scenes, Plano’s environmental team was counting larvae, testing water samples, and logging every movement.

At first, results were modest: a 15% reduction in mosquito larvae near the release sites. Not enough to make headlines — yet.

But locals started noticing something different. Evening walks weren’t as miserable. Kids were playing outside again. The swarms near the ponds were thinning.

By week three, the fish population had doubled. Female mosquitofish give birth to live young, and the newborns were already hunting. Nature was doing what chemicals couldn’t — adapting.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

At week six, the results shocked everyone.

Mosquito larvae counts at Pecan Hollow had dropped by 67%, and the Parkway site by 71%. The air traps used to catch adult mosquitoes showed nearly 50% fewer insects overall.

Plano had achieved in weeks what years of pesticide fogging never could.

Residents began reporting life returning to normal. Barbecues, soccer games, joggers — all back without the constant slapping and scratching.

Even better, the fish weren’t staying put. They followed drainage channels into nearby ponds, establishing new colonies on their own. Plano’s experiment was spreading naturally — and successfully.

From Mockery to Model

Within three months, the turnaround was undeniable.

The mosquito population had plummeted more than 80% in many neighborhoods. West Nile cases declined sharply. The fish required no further maintenance, no re-stocking, and no chemical follow-ups.

The city’s mosquito control budget was slashed by more than half — from nearly $50,000 a year in chemical spraying to just a fraction for the fish program.

Even more impressive, the ecosystem stayed stable. The mosquitofish didn’t overpopulate or disrupt native species. They simply filled a natural predator niche that had been left vacant.

The internet, once mocking, now marveled. Posts praising Plano’s “miracle fish” racked up thousands of likes. Former critics deleted old tweets. Memes that once ridiculed the project were replaced by triumphant ones: fish in cowboy hats captioned “Told you so.”

The Ripple Effect

Soon, other Texas cities came calling. Dallas, Frisco, McKinney — all wanted to know how Plano pulled it off.

Heineka found himself presenting at environmental conferences and city meetings. The fish that once made him a laughingstock were now state heroes.

Even the CDC took notice. Researchers began analyzing Plano’s data as a potential model for vector control nationwide.

By year’s end, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Arkansas had launched pilot programs of their own. International health organizations studying malaria, dengue, and Zika reached out, exploring how similar ecological solutions could reduce mosquito-borne diseases worldwide.

The economic impact was also impossible to ignore. With fewer mosquitoes, outdoor recreation boomed. Real estate agents began touting “mosquitofish-protected ponds” in listings. Hotels reported higher summer bookings.

A tiny fish had created an economic ripple larger than anyone expected.

The Critics Return — With Good Questions

Success brought a new kind of scrutiny.

Some scientists cautioned that not every pond was ideal. The fish needed vegetation to breed and moderate temperatures to survive. Extreme winters or droughts could threaten their populations.

Others worried about genetic diversity. If all the mosquitofish came from the same hatchery stock, inbreeding could weaken future generations.

Heineka’s team took these critiques seriously. They diversified their breeding sources, established genetic management protocols, and created assessment tools for other cities.

What began as an experiment had evolved into a blueprint for sustainable pest control.

Three Years Later

By 2018, Plano’s mosquito population was still down 75–80% from pre-program levels. West Nile cases had plummeted. And the fish — the same ones once dismissed as “a waste of taxpayer money” — had built thriving, self-sustaining colonies in dozens of ponds.

The city’s mosquito control costs were permanently reduced, and its air was cleaner without chemical fogs.

Plano’s mosquitofish program had gone from a punchline to a case study in environmental science.

Universities across Texas added it to their environmental engineering curricula. Public health departments cited it as proof that “working with nature, not against it,” could solve modern ecological problems.

The Moral of the Story

Texas took a chance on an idea that sounded too simple to work — and it paid off.

In a world addicted to quick chemical fixes, Plano’s mosquitofish reminded us that sometimes, the smallest creatures can make the biggest difference.

Today, those same fish continue to swim through Texas ponds, silently keeping mosquito populations in check — and reminding everyone that sometimes, being laughed at is the first step toward changing the world.

So the next time someone mocks a wild idea, remember Plano.

They threw fish at mosquitoes — and won.